Shocking figures

Last week’s GDP report had plenty of them: a 10% annual GDP drop (the largest on record); and output still 6.3% below its pre-pandemic peak (roughly equal to the financial crisis). But that masks resilience and business adaptation. GDP grew 1.2% in December, rebounding from November’s lockdown. It meant that the economy grew in Q4, avoiding a double-dip recession. Construction and manufacturing grew at decent pace in the final quarter, while the recovery continued in much of the professional and business services space (in stark contrast to the consumer-facing bits). There’s a big repair job on, but there are signs it can be achieved.

Tight belts

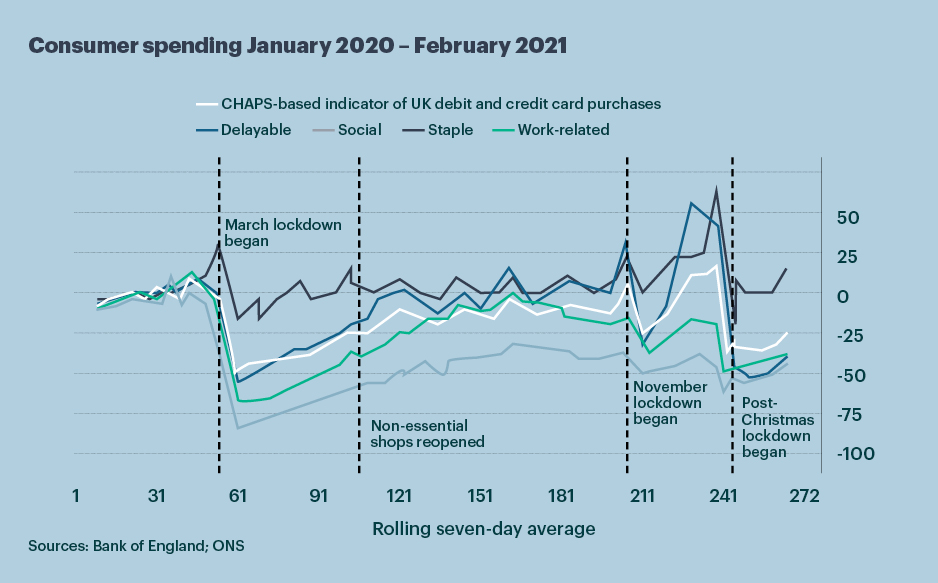

An outsized drop in household spending lies behind much of the UK’s economic malaise. Government expenditure and business investment both continued to climb in Q4 2020, with the former now above pre-pandemic levels. But as the second wave struck, households trimmed their outgoings, leaving consumption spending 8.4% lower than a year before. Lockdowns and tiered regional restrictions meant spending in restaurants and hotels fell by a fifth. Still, the flipside of our abstemious behaviour is that (some) households have accumulated substantial extra savings that could power the recovery when it comes.

Slowly, slowly

The temperature may be bitter, but the latest economic indicators have a faint hint of sweetness. Card spending rose 8% in the week to 4 February, helped by the month-end pay day and, perhaps, the cold snap – cupboard stocking as spending on staples was 13% higher than a year before. The share of business trading rose a touch (three percentage points), as did online job ads (two percentage points). And you’ve probably noticed, but traffic was slightly busier, too. Add to that the 14.5m people having the first jab and infection rates the lowest since last autumn/early winter. Slowly, it’s coming.